About Brain Imaging

Why Is Brain Imaging a Hot Topic?

Recent advances in brain-imaging

technology — notably

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fMRI (functional magnetic resonance

imaging) — are allowing medical scientists not only to detect

anatomical brain abnormalities such as tumors and cysts, but also

to diagnose various functional losses in the brain caused by stroke,

traumatic injury, or neurological disease. It is even becoming possible

to associate specific brain areas with certain behavior, emotions,

and psychological traits. As promising as these developments are,

they also raise thorny ethical questions: How far should we permit

science to go in analyzing human thoughts and emotions? How could

the findings be misused? Under what conditions does brain scanning

become like mind reading — and

pose the ultimate threat to personal privacy?

|

|

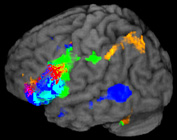

| Functional imaging during language tasks. Different brain areas are involved in specific aspects of language. (courtesy M. Mesulam) |

Is it all in your head?

Neurologists know that damage to the brain can change personality and behavior.

These changes often take the form of extreme nonconformity to social norms: excessive aggression, a lack of empathy, inability to control impulsive or inappropriate feelings and speech, etc. Using brain-imaging devices, some experimenters are trying to pinpoint the areas of the brain that are activated when people react to ideas or stimuli: Exactly where and how does the brain process thoughts on provocative issues like crime, racism, or injustice, for instance? Are anger, fear, joy, love, or sorrow detectable in the brain by any physical means? What does a lie “look” like in the brain? This research assumes that by peering into the brain, science can begin to answer these questions; but underlying this assumption is a broader one — namely, that the brain and the mind are essentially one and the same.

“My underdeveloped brain made

me do it!”

As

imaging technologies make the brain more accessible to scientific

study and potentially more revealing of the personality than ever,

some long-standing questions about the nature of human behavior may

be reframed in “neuroethical” terms.

For example, if the ability to tell right from wrong springs from

observable, measurable activity in the brain, can we conclude that

moral sensibility is inborn? Can environmental factors such as parenting

or privilege fundamentally alter this and other brain-based capacities?

If an MRI shows any part of a person’s brain to be abnormal,

can he or she be expected to behave according to societal norms? The

brain science experts participating in the “Imaging the Brain,

Reading the Mind” discussion will

describe in accessible terms how images of the brain are acquired

and what kinds of information they can reliably provide. Further they

will discuss the ethical and social implications of attempts to read

people's thoughts, attitudes, and personalities using brain imaging.